Despite the fact that Mark Rutte's VVD (People's Party For Freedom & Democracy)-led government resigned two months ago over a scandal involving extensive child welfare fraud, Dutch voters returned his coalition government to power and with an increased majority overall, after counting the seat totals of the component parties.

The VVD in fact increased its seat total by 2 to 35, although much of its increase came in the commuter belts around the Randstad conurbation and in the central Netherlands. In progressively inclined municipalities, especially university cities, the VVD's vote actually decreased somewhat. Much of the VVD's vote increase came in municipalities where the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) used to be the "plural force" (the party achieving the most votes in that municipality; political dominance does not exist in the accepted sense of the term in Dutch politics), although as I explained in my analysis of the 2017 Dutch general election long-term demographic change and increasing secularity are also responsible for the continuing decline of the CDA long term. Meanwhile the centrist and urbane Democrats 66, who were during the last 3 years predicted to lose heavily due to their decision to enter into a coalition with VVD, were in fact rewarded with an extra 4 seats, twice the increase the VVD managed, and topped the poll in the majority of Dutch cities.

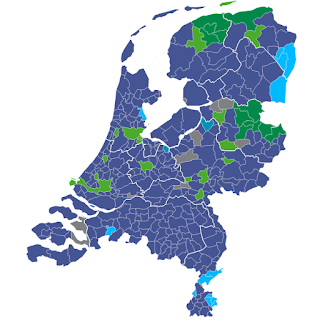

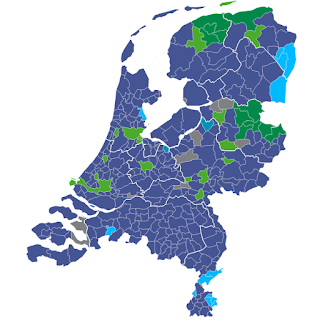

Parties on the "left" had a very poor night in the Netherlands. GroenLinks (Green Left) which in the last four years was rapidly displacing other progressive parties in the Netherlands ended up losing 6 seats, leaving them with 8, although proportionally this is not as bad as their setback in 2012. Some of its more hardline voters defected to the Party for the Animals (PvdD) where there is significant overlap in terms of environmental issues; PvdD gained a seat giving them 6, their best total ever. However, the rise of Volt Netherlands, a strongly pro-European liberal party, was the biggest factor in GL's decline. Volt Netherlands won a total of 3 seats but found few friends outside university cities and the Dutch capital of Amsterdam. Volt's best result was in Waginingen, which was also the only municipality where GL finished second; in the municipalities where GL topped the poll in 2017 they finished third in every such case and were displaced as poll-toppers by the Democrats 66. Also, in those cases Volt's vote was at least twice their overall result of 2.4% across the Netherlands. The Labour Party (PvdA), having suffered a drubbing in 2017, made no progress in seat terms and remained on 5.7%; keep in mind that 2017 was their worst ever year. There were also few municipalities with any noticeable increase in their support. They and the Socialist Party (SP), the latter of which lost 5 seats bringing it down to 9 and which only finished second in two municipalities in Groningen (Eemsdelta, and Pekela), are like the CDA enduring a long-term decline and are winning little support amongst newer and more diverse generations of Dutch voters who are opting for newer progressive parties. In fact as the map below demonstrates not a single Dutch party of the "left" won any of the municipalities this year:

(Colour guide: dark blue = VVD, emerald green = CDA, light blue = PVV, grey = SGP)

As for the hardline nationalist section of Dutch politics, that proved more split than ever before. PVV (Party for Freedom), lost 3 seats bringing them down to 17, although surprisingly they retained third place in the polls. The Forum for Democracy was set to displace them as the primary "nationalist right" party in the Netherlands but a series of scandals in 2020 (especially its youth wing being exposed as having glorified mass murderers Anders Breivik and Brenon Tarrant) tarnished their image amongst lapsed CDA/PvdA/SP voters (where PVV et al. primarily get their support base amongst those voters who are not explicitly racist and anti-immigration) and saw FvD themselves be hit by a splinter group, JA21 (Juiste Anwoord 21), which had been founded only three months prior to this election. JA21 nevertheless took all 3 of FvD's MEPs and the majority of its provincial councillors to boot after a referendum on whether to expel FvD's leader, Thierry Baudet, from FvD failed by 24%-76%. The long-term decline of PVV nevertheless saw FvD gain 6 seats, although its support base is very different to the PVV's. The PVV did top the poll in a few municipalities but the majority of these were in relatively poor and industrial areas on the border with Germany, particularly Limburg, whereas the FvD found its support increasing most strongly in the Dutch "Bible belt" where the Calvinist Reformed Political Party (SGP) garners the vast majority of its support, and also where the nearly as conservative Christian Union (CU) is strongest. JA21's support was less correlated with SGP support but was correlated with rises in FvD support. Vote splitting also occured with the pensioners' party, 50PLUS, which lost all but one seat. Its former leader Henk Krol, who left 50PLUS after arguments with the party's leadership, formed his own list but it received a derisory vote share of 0.09%.

The other two new parties in the Tweede Karmer (Dutch Parliament) are BIJ1 (formerly called Article 1, after the same article in the Dutch constitution that prohibits discrimination) and BBB (the Farmer-Citizen Movement, primarily an agrarian party), who gained 1 seat each thanks to concentrated support in key areas. BIJ1 gained significant support in municipalities with substantial Afro-Dutch populations (but very little support elsewhere), and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement invigorated its support in and around Amsterdam in particular. BBB's support meanwhile, as you would expect, was concentrated in rural municipalities some distance from the cities, especially in the largest province, Gelderland, which is also where the CDA lost the most support and where the farmers' protests of last year were most prominent in the Netherlands. Since the Netherlands elects from a single nationwide constituency for all 150 parliamentary seats, geographical concentrations of support generally do not reward small parties the way they would in most countries, but in both BIJ1's and BBB's cases that proved crucial to their entry to the Tweede Karmer.

Amidst all these splits and new parties, some things did not change in Dutch politics. The SGP, the oldest Dutch political party, retained its 3 seats despite the inroads made by FvD in particular, and CU also retained its 5 seats, again thanks to support in the Protestant Bible belt (amongst moderate Catholics in the Netherlands, the CDA is much more popular than CU). Denk also retained its 3 seats despite controversy over its links to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, which has led it to being dubbed "the long arm of Ankara", and the rise of BIJ1 whose leader, Silvana Simons, was originally part of Denk but later left.

With 17 parties in the Tweede Karmer, this Dutch parliament is the most multiparty ever. However, even with an effective threshold of 0.67%, some parties inevitably fail to get a seat. Notably, the Blank List, or List 30, known for COVID-19 scepticism, fell well short of the de facto threshold with just 0.08% of the vote. The list of parties that failed to win a seat include as many as 15 new parties, of which the syncretic and pro-direct democracy Code Orange came closest. The wooden spoon in this Dutch election went to The Greens, a group of hardline environmentalists who refused to merge into GreenLeft when it was founded from a merger of small radical parties back in 1989; the Greens, running in their first Dutch general election since 1994, polled just 112 votes.

As with most countries in the world the coronavirus pandemic dampened turnout, but not by much in this case, since turnout at 78.54% was still respectable by Dutch standards and is good by normal democratic standards. It is also clear that the Rutte government's handling of the coronavirus crisis in the Netherlands, one of the most densely populated countries in the world (viruses spread more easily in heavily built-up areas), has been rewarded by the electorate.

Comments

Post a Comment