On the Dutch general election of 2017

The Dutch general election of 2017 finally concluded earlier today when the last of the Netherlands' 388 municipalities (which genuinely cover areas as local as possible and are not drawn for administrative convenience, unlike many principal authorities in England) finished counting the votes.

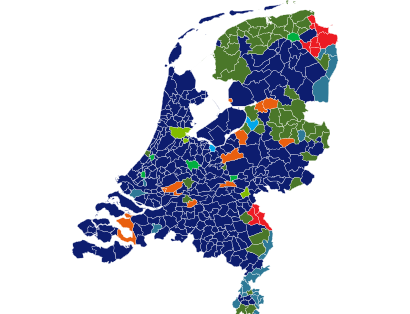

This map shows which party topped the poll by municipality (blue=VVD, dark green=CDA, light green=GL, red=SP, turquoise=PVV, light blue=CU, orange=SGP).

Like so many people, I am pleased with GroenLinks' record result, although unfortunately they could only finish in sixth place in the end, just behind the Socialist Party (SP), rather than the third place finish many Dutch polls anticipated and in spite of the increased attention their lijsttrekker (list topper, or leader), Jesse 'Jessiah' Klaver was getting in the run-up to the election. They managed 8.9% and 14 seats (and thus got 3 1/2 times their 2012 seat total, not quadruple as some online commentators misleadingly claimed before the counting had actually finished), which is their best ever total but still behind key rivals who they hoped to beat, like the Democrats66 (traditional liberals), and the Socialist Party (traditional socialist). Why did this happen?

The high level of competition between those aiming for the collapsing PvdA (Dutch Labour Party, social-democratic) vote, especially in university cities and the capital, Amsterdam, was a key cause, even though student voter turnout in some prestigious and specialist Dutch universities reached approximately 100%, or at least 90%. GroenLinks topped the poll in only two municipalities, which included Amsterdam (GL polled 19.6%) and the Netherlands' oldest city, Nijmegen (GL polled even better than in Amsterdam with 20.1%). D66, however (which strongly competes with GL for the liberal, free-thinking and cosmopolitan vote) beat them to pole position in the cities of Groningen, Utrecht, and Leiden (all host to prestigious universities as well; GL's best performance was in Utrecht with 20.2%). They did however win over many would be Socialist Party voters who saw GroenLinks as more progressive and more in tune with the young generation, even in more working-class Groningen municipalities like Oldlambt and Menterwolde, and also in northern Limburg. The rise of PvdD (the Dutch animal rights party), which managed 5 seats, also its best ever total, took some more moderate environmentally-minded voters; PvdD leader Marianne Thieme is a professed Seventh-Day Adventist which is a boon to environmentally-minded Christians outside the major cities (Jesse Klaver did once lead the Christian Federation of Trade Unions, CNV, but is nowhere near as evangelical in religious terms)

The junior coalition partners in the last government, PvdA, were undoubtedly the biggest losers in this election, and were set to be almost from the moment they joined forces with the liberal-conservative VVD ('Orange Book' liberals similar to Germany's FDP) in the previous government, which to its partial credit managed a full term without a snap election when none of the cabinets of 2002-12 did (including the first of Mark Rutte's cabinets and all of former PM Jan Peter Balkende's cabinets). PvdA failed to come first, or even second, in a single municipality and as a punishment for their collusion with the centre-right VVD, they dropped from 38 seats to a derisory 9, and seventh place to boot behind GroenLinks. Their vote collapsed most spectacularly in their working-class strongholds in the north and in the 'Randstad' metropolitan region, the less prosperous province of Limburg where the radical right Party for Freedom (PVV) made its strongest surges, especially at the southern tip close to the industrial Ruhr region of Germany, and in rural, more Christian areas they had an even worse time. Their collapse is as reminiscent of the Labour Party in Ireland last year (who fell from 37 seats to 7 in 2016), and effectively finishes them as a major force in the Dutch political scene. The governing VVD lost only 8 seats, now giving them 33, but still finished first despite only polling 21.2%, the second-lowest ever in the Netherlands for a party that topped the poll nationally (they also set the record for lowest ever 1st place finish in 2010, where they managed 20.5%).

Contrary to popular belief, the Netherlands did not get be-Wildered as some feared. Geert Wilders, despite having pushed PVV to first place in some polls, in the end only managed to increase PVV's vote share by 3%, which gave them only 20 seats, just 5 more than in 2012. This is not even PVV's best result, since in 2010 they managed 24 seats. Not only did Geert Wilders bungle his campaign a la Paul,Nuttall in Stoke on Trent Central, but also the increased speculation about whether PVV could obstruct attempts to form a new government (since no other political party in the Netherlands will form a coalition with them or help Geert Wilders become PM) mobilised the progressive and moderate opposition across the Dutch political spectrum more than ever before-the CDA and VVD in the villages and towns, and D66 and GL in the cosmopolitan cities. PVV's vote was also split by a new party, Forum for Democracy, which with its advocacy of direct democracy, an EU membership referendum and national conservative stance is giving the Dutch an equivalent of the Swiss People's Party (still very popular in Switzerland). FvD managed only 1.8% and 2 seats but this exceeded even their expectations, given that they were only formed last year.

Despite high hopes, D66 only managed fourth place, just 0.3% behind the Christian Democratic Appeal, the traditional moderates of Dutch politics, and equal in seat totals (both managed 19 seats). However, the CDA's performance is merely a recovery of unsatisfied VVD voters rather than a resurgence, and like Fianna Fail in Ireland, is unlikely ever to have the same dominance or impact in Dutch politics for the foreseeable future. Many of their older voters have turned to the pensioners' interests party, 50PLUS, which doubled its seat total to 4 this year.

The Socialist Party is experiencing a similar long-term problem to that of the CDA. Due to the fact that 13 parties will now be represented in the Dutch House of Representatives instead of 11, they lost 1 seat despite their vote share only dropping by 0.4%. They have managed to gain many middling and older PvdA voters in Groningen province (but not the city of Groningen itself where their better-educated base was hit hard by GroenLinks), but are fading fast in Limburg, for even in Gennep, Boxmeer and Bergen, the three municipalities in that province where they topped the poll, their vote share decreased not insignificantly. They are also failing to capture many younger voters, partly due to their Eurosceptic stance and more traditional left-wing economic stances, and are not seen as progressive or internationalist as GL. Even where the contests were only between VVD/CDA/PVV, the Socialists made no overall progress from PvdA's collapse, which almost universally in those areas went to GL or PVV depending on the relative prosperity of the area.

As predicted, the Christian Union (Orthodox Protestants) and the Reformed Political Party (SGP, hardline Calvinists) stayed static in terms of vote share and seat totals (5 and 3) but remained strong in the Dutch 'Bible belt'; even though the CDA's conservative platform is not specifically orientated towards one branch of Christianity over another, it is much more attractive to Catholic voters in practice. The newest party to enter the Dutch House of Representatives is Turkish and Moroccan minority interests' party DENK (Dutch for 'think' and Turkish for 'equality'), which gained 2.0% and the vote and 3 seats. There is no 'electoral threshold' in the Netherlands; a party only needs to win enough votes for 1 full seat (0.67% of the vote) to qualify for representation. The controversy over attempts by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to influence the Netherlands, which resulted in all Dutch ambassadors to Turkey being expelled from that country in response, did not cause DENK the harm it could have done in spite of the international negative publicity it received, and (unverified) rumours that DENK is merely a 'front' for Erdogan.

Turnout was 80.4%, which is par for the course in Dutch politics; in spite of proportional representation and a wide spectrum of political parties the turnout/abstention rate remains largely the same election after election. This Dutch parliament is the most politically colourful ever, with 13 different parties being represented, and with at least 2 seats. In the only comparable example, that of 1982, 12 different parties achieved representation but 3 of them only achieved 1 seat apiece, and this was before the component parties of GroenLinks and the Christian Union had merged (the mergers happened in 1989 and 2000 respectively). This is also the first time a party dedicated to minority rights has been formally represented in the Netherlands, meaning the Dutch political spectrum is wider than ever, particularly with 1.5% of the votes cast going to parties that did not win any seats.

Cabinet formation will be interesting, to say the least. It has been rightly claimed that sticking to principles and values helped GL achieve their best ever result in this election. If this maxim is to remain true, however, then Jesse Klaver and GL should avoid joining any coalition headed by Mark Rutte (almost certain to remain Dutch Prime Minister) at all costs.

This map shows which party topped the poll by municipality (blue=VVD, dark green=CDA, light green=GL, red=SP, turquoise=PVV, light blue=CU, orange=SGP).

Like so many people, I am pleased with GroenLinks' record result, although unfortunately they could only finish in sixth place in the end, just behind the Socialist Party (SP), rather than the third place finish many Dutch polls anticipated and in spite of the increased attention their lijsttrekker (list topper, or leader), Jesse 'Jessiah' Klaver was getting in the run-up to the election. They managed 8.9% and 14 seats (and thus got 3 1/2 times their 2012 seat total, not quadruple as some online commentators misleadingly claimed before the counting had actually finished), which is their best ever total but still behind key rivals who they hoped to beat, like the Democrats66 (traditional liberals), and the Socialist Party (traditional socialist). Why did this happen?

The high level of competition between those aiming for the collapsing PvdA (Dutch Labour Party, social-democratic) vote, especially in university cities and the capital, Amsterdam, was a key cause, even though student voter turnout in some prestigious and specialist Dutch universities reached approximately 100%, or at least 90%. GroenLinks topped the poll in only two municipalities, which included Amsterdam (GL polled 19.6%) and the Netherlands' oldest city, Nijmegen (GL polled even better than in Amsterdam with 20.1%). D66, however (which strongly competes with GL for the liberal, free-thinking and cosmopolitan vote) beat them to pole position in the cities of Groningen, Utrecht, and Leiden (all host to prestigious universities as well; GL's best performance was in Utrecht with 20.2%). They did however win over many would be Socialist Party voters who saw GroenLinks as more progressive and more in tune with the young generation, even in more working-class Groningen municipalities like Oldlambt and Menterwolde, and also in northern Limburg. The rise of PvdD (the Dutch animal rights party), which managed 5 seats, also its best ever total, took some more moderate environmentally-minded voters; PvdD leader Marianne Thieme is a professed Seventh-Day Adventist which is a boon to environmentally-minded Christians outside the major cities (Jesse Klaver did once lead the Christian Federation of Trade Unions, CNV, but is nowhere near as evangelical in religious terms)

The junior coalition partners in the last government, PvdA, were undoubtedly the biggest losers in this election, and were set to be almost from the moment they joined forces with the liberal-conservative VVD ('Orange Book' liberals similar to Germany's FDP) in the previous government, which to its partial credit managed a full term without a snap election when none of the cabinets of 2002-12 did (including the first of Mark Rutte's cabinets and all of former PM Jan Peter Balkende's cabinets). PvdA failed to come first, or even second, in a single municipality and as a punishment for their collusion with the centre-right VVD, they dropped from 38 seats to a derisory 9, and seventh place to boot behind GroenLinks. Their vote collapsed most spectacularly in their working-class strongholds in the north and in the 'Randstad' metropolitan region, the less prosperous province of Limburg where the radical right Party for Freedom (PVV) made its strongest surges, especially at the southern tip close to the industrial Ruhr region of Germany, and in rural, more Christian areas they had an even worse time. Their collapse is as reminiscent of the Labour Party in Ireland last year (who fell from 37 seats to 7 in 2016), and effectively finishes them as a major force in the Dutch political scene. The governing VVD lost only 8 seats, now giving them 33, but still finished first despite only polling 21.2%, the second-lowest ever in the Netherlands for a party that topped the poll nationally (they also set the record for lowest ever 1st place finish in 2010, where they managed 20.5%).

Contrary to popular belief, the Netherlands did not get be-Wildered as some feared. Geert Wilders, despite having pushed PVV to first place in some polls, in the end only managed to increase PVV's vote share by 3%, which gave them only 20 seats, just 5 more than in 2012. This is not even PVV's best result, since in 2010 they managed 24 seats. Not only did Geert Wilders bungle his campaign a la Paul,Nuttall in Stoke on Trent Central, but also the increased speculation about whether PVV could obstruct attempts to form a new government (since no other political party in the Netherlands will form a coalition with them or help Geert Wilders become PM) mobilised the progressive and moderate opposition across the Dutch political spectrum more than ever before-the CDA and VVD in the villages and towns, and D66 and GL in the cosmopolitan cities. PVV's vote was also split by a new party, Forum for Democracy, which with its advocacy of direct democracy, an EU membership referendum and national conservative stance is giving the Dutch an equivalent of the Swiss People's Party (still very popular in Switzerland). FvD managed only 1.8% and 2 seats but this exceeded even their expectations, given that they were only formed last year.

Despite high hopes, D66 only managed fourth place, just 0.3% behind the Christian Democratic Appeal, the traditional moderates of Dutch politics, and equal in seat totals (both managed 19 seats). However, the CDA's performance is merely a recovery of unsatisfied VVD voters rather than a resurgence, and like Fianna Fail in Ireland, is unlikely ever to have the same dominance or impact in Dutch politics for the foreseeable future. Many of their older voters have turned to the pensioners' interests party, 50PLUS, which doubled its seat total to 4 this year.

The Socialist Party is experiencing a similar long-term problem to that of the CDA. Due to the fact that 13 parties will now be represented in the Dutch House of Representatives instead of 11, they lost 1 seat despite their vote share only dropping by 0.4%. They have managed to gain many middling and older PvdA voters in Groningen province (but not the city of Groningen itself where their better-educated base was hit hard by GroenLinks), but are fading fast in Limburg, for even in Gennep, Boxmeer and Bergen, the three municipalities in that province where they topped the poll, their vote share decreased not insignificantly. They are also failing to capture many younger voters, partly due to their Eurosceptic stance and more traditional left-wing economic stances, and are not seen as progressive or internationalist as GL. Even where the contests were only between VVD/CDA/PVV, the Socialists made no overall progress from PvdA's collapse, which almost universally in those areas went to GL or PVV depending on the relative prosperity of the area.

As predicted, the Christian Union (Orthodox Protestants) and the Reformed Political Party (SGP, hardline Calvinists) stayed static in terms of vote share and seat totals (5 and 3) but remained strong in the Dutch 'Bible belt'; even though the CDA's conservative platform is not specifically orientated towards one branch of Christianity over another, it is much more attractive to Catholic voters in practice. The newest party to enter the Dutch House of Representatives is Turkish and Moroccan minority interests' party DENK (Dutch for 'think' and Turkish for 'equality'), which gained 2.0% and the vote and 3 seats. There is no 'electoral threshold' in the Netherlands; a party only needs to win enough votes for 1 full seat (0.67% of the vote) to qualify for representation. The controversy over attempts by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to influence the Netherlands, which resulted in all Dutch ambassadors to Turkey being expelled from that country in response, did not cause DENK the harm it could have done in spite of the international negative publicity it received, and (unverified) rumours that DENK is merely a 'front' for Erdogan.

Turnout was 80.4%, which is par for the course in Dutch politics; in spite of proportional representation and a wide spectrum of political parties the turnout/abstention rate remains largely the same election after election. This Dutch parliament is the most politically colourful ever, with 13 different parties being represented, and with at least 2 seats. In the only comparable example, that of 1982, 12 different parties achieved representation but 3 of them only achieved 1 seat apiece, and this was before the component parties of GroenLinks and the Christian Union had merged (the mergers happened in 1989 and 2000 respectively). This is also the first time a party dedicated to minority rights has been formally represented in the Netherlands, meaning the Dutch political spectrum is wider than ever, particularly with 1.5% of the votes cast going to parties that did not win any seats.

Cabinet formation will be interesting, to say the least. It has been rightly claimed that sticking to principles and values helped GL achieve their best ever result in this election. If this maxim is to remain true, however, then Jesse Klaver and GL should avoid joining any coalition headed by Mark Rutte (almost certain to remain Dutch Prime Minister) at all costs.

Makes you realise what real democracy is. Even the Coronation on the new king is a modest informal affair. - what a pity our Elizabeth 2nd can't die and King Wilhelm Alexander come over and immediately sack Parliament. - seriously looking at moving the Zeeland and letting England rot like it deserves.

ReplyDelete